Ultraportable handheld ultrasound (HHU) devices are being rapidly adopted by emergency medicine (EM) physicians. Though knowledge of the breadth of their utility and functionality is still limited compared to cart-based systems, these machines are becoming more common due to ease of use, extreme affordability, and improving technology.

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is ubiquitous in emergency departments (EDs) and recognized as the standard of care in the workup of multiple disease processes encountered by the emergency physician (EP). In addition to its recognition as a workhorse for diagnosis and procedural guidance, POCUS is increasingly used by other medical specialties, ancillary staff, and first responders. POCUS is increasingly used outside the clinical setting as a tool for teaching practitioners-in-training with ultrasound instruction integrated into medical school curricula.

Technological advances have led to the introduction of truly handheld ultrasound (HHU) into the POCUS market. With smaller footprints, user-friendly interfaces, and lower price points, the broad appeal of these devices is clear. However, as with most emerging technology in healthcare, the advent of HHU devices brings a host of clinical and academic potential as well as new challenges and complex questions about the handling of patient data.

While numerous HHU devices are available, and large, robust data to support their interchangeable use with the traditional machines is lacking the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) released a consensus statement recognizing HHU-generated images as “comparable” to those of traditional machines. In order to better navigate the myriad handheld devices, this paper will serve as an overview of what is currently known about HHU devices: the mechanics of how they work, nuances of their use in practice, how they compare to traditional machines, and what this technology portends for the future of POCUS in the ED and beyond.

Several HHU devices are currently available. A comparison of specifications between several devices can be found. The image-generating technology between handhelds and traditional machines is similar with one exception. To create ultrasound images, traditional cart-based ultrasound systems and most handhelds use piezoelectric crystal technology. The product from BMV Technology Co., Ltd., however, utilizes capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducers on complementary metal-oxide semiconductors, or CMUT-on-CMOS technology. CMUTs replace the traditional vibrating piezoelectric crystals with oscillating drums embedded in a single silicon chip, serving the same function of converting electricity into sound waves. In addition to decreasing the cost of production, this technology allows a single device to operate at a wider range of frequencies, negating the need for multiple probes.

Handheld products come as single or multiple probe devices. MX3 and MX9 offer two separate heads on a single probe, increasing the range of studies that can be performed by simply rotating the probe. While some products have the ability to display generated images on personal smart devices, others utilize proprietary displays sold with the product, which may hold much of the processing power of the system. Connectivity between the probe and the display varies between products. Some HHU probes connect through a traditional cable system, while some products offer wireless communication. The MX9 devices can stream their images live to multiple displays simultaneously.

Future of Handhelds in the ED

Remotely guided US, or “tele-ultrasound,” improves image quality and scanning confidence among novice users and will be critical for improving safety as HHU becomes more widespread. AI algorithms have been developed that automatically show users the movements necessary to obtain high-quality images. Use of neural networks in computer science also has significant implications for POCUS. Many HHU devices already possess AI functions such as automated calculation of ejection fraction and bladder volume . Zhang et al. created a fully automated echocardiography interpretation algorithm that functions with B-mode images obtained by HHU . Thus, practitioners using machines lacking advanced echocardiography functionality or high-end image quality may still use HHU devices to answer cardiac-related clinical questions due to these advances in AI and smart device processing power. The combination of widespread HHU availability, evolving tele-ultrasound capabilities and machine learning algorithms paints a promising picture for patient care with earlier, more accurate disease detection from even novice users, in any geographic location.

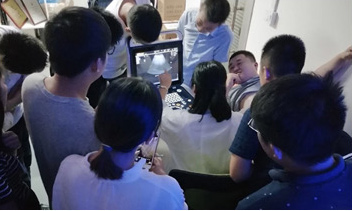

Concordant with advances in tele-ultrasound, virtual POCUS education has recently become feasible. Technologies inherent in some HHU devices allow for remote image viewing and thus remote peer-review and QA. HHU devices saw increased use as adjuncts to resident education during the COVID-19 pandemic due to their compatibility with virtual platforms. Research on the efficacy of this emerging facet of medical education is currently extremely limited but likely to expand in the face of restrictions on in-person learning during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

HHU will likely see increased future use by ED consultants, including specialties that are not traditional users of POCUS (e.g., nephrology, internal medicine). The likelihood that HHU devices will become ubiquitous outside the ED relatively soon has led some to suggest that US should become a routine part of the physical examination. As US education is increasingly incorporated into medical school curricula, it is likely to make specialty-specific training and implementation at the graduate level easier and more widespread.

The use of HHU devices by consultants offers many potential benefits for patient care. In an office-based setting, it could be used to identify conditions requiring urgent ED referral (e.g., large pericardial effusion) versus those appropriately treated in the outpatient setting (e.g., cellulitis without abscess). In the inpatient setting, HHU could be used to track serial changes in a patient’s condition, such as pulmonary edema, from arrival in the ED until discharge from the floor. Alternatively, consultants could use HHU devices to perform focused examinations to answer limited questions—has left ventricular ejection fraction decreased or does the patient with known cholelithiasis now have findings suggestive of acute cholecystitis? Rapid answers to these direct questions, particularly with consultants at the bedside, could facilitate treatment and disposition decisions while reducing the burden on sonographers and interpreting physicians.

While it is highly plausible that HHU use can improve patient care, demonstration of such benefit with formal research studies will strengthen the argument for widespread implementation and direct its use to the areas with the greatest potential impact. Several preliminary studies suggest the benefits of HHU use. These include reduced need for follow-up testing when used in the outpatient setting, with a low incidence of false negatives (5%), faster time to diagnosis, and reduced time to first intervention when HHUs were used by rapid response teams. While image interpretability appears similar between HHUs and cart-based systems, a critical concept for future studies is not to conflate image quality and the setting of use with operator training and skills. Maintenance of rigorous educational programs and adequate quality assurance are crucial as device availability increases.